Australian surfer Darren Longbottom went to the Ments and all he got was a lousy wheelchair…

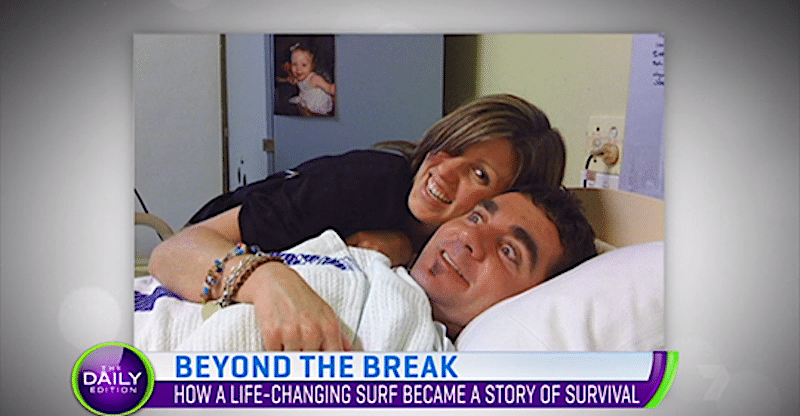

Ten years ago, the hard-charging big brother of shaper and pro Dylan Longbottom, flew to the Menatwais for a little r and r, hit his head on his board and wound up losing the spark that powered his four limbs.

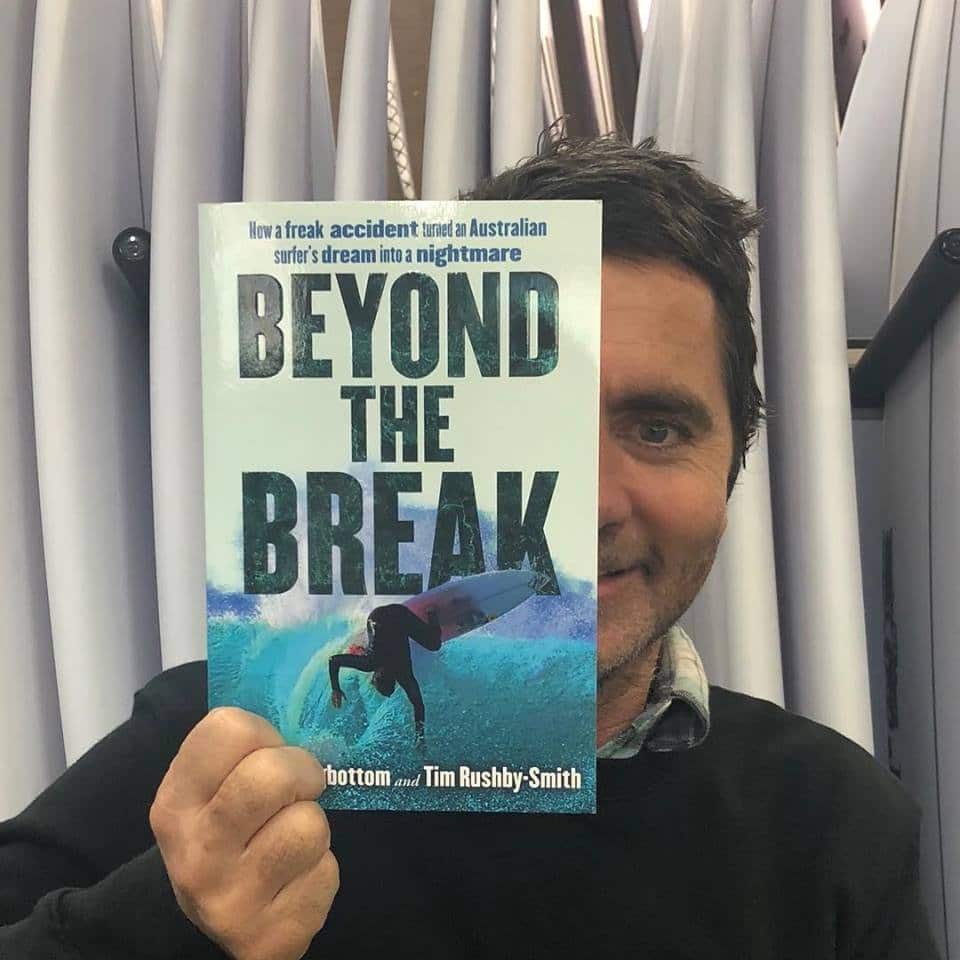

Darren Longbottom, who is now forty six, has a couple of kids, owns surf shops which he stocks with his little bro’s boards and powers around in a metal chair. He also co-wrote a book called Beyond the Break: How a freak accident turned an Australian surfer’s dream into a nightmare.

It’s an ultimately uplifting story, I suppose, “survival against the odds” and so forth, but it sends shivers along my mercifully still functioning spinal cord.

The hurt. The despair. It’s a mighty slashing underscore.

As Dylan told The Sydney Morning Herald,

“He’s been through so much. His wife left him a year and a half after the accident. But still, I never saw him angry, even at the beginning, after the accident. I would have been angry, but he actually went the opposite way. He mellowed out. He became more accepting of people, less critical of them, more patient. I felt so sorry for him, seeing him in the chair. Then he’d say, “I surfed for 33 years, which is more than most people surf in their lifetime. I’ve had so many waves!” And he was content with that. That’s his strength, to be able to look at it that way.”

This extract is called Moment of Impact.

Blue water. Blue water and silence … And then, BOOM!

It was as if someone had turned on the television with the volume set at its highest level, a flood of visions from my life flickering by at lightning speed, stuffing thirty-five years into a few seconds. It is a heavy, heavy feeling. My wife, Aimee, and my daughter, Bowie … back further … our old house in Cronulla … Christmas at my grandparents’ riding skaties with Dylan and Danny … pulling stupid faces at every soccer team photo. And now, not alive, just drifting in a vacuum.

A huge surge of energy came without warning and hit me like an electric shock. I took my first breath after what felt like an eternity. I was awake and in water, bobbing like a cork. The shock was the burst of adrenaline, pulling me back from the edge of nothing. I struggled to work out what was happening, before I was back under water and sinking. Why was I sinking? Why couldn’t I get back to the surface? I was swimming, for God’s sake, and I’m a good swimmer, kicking as hard as I could, willing myself, telling myself to surface.

What’s happening? Swim, you idiot, get back to the surface.

My head finally broke through into the air, and I felt that enormous surge of energy again, another shock, as I took another breath.

My thoughts were still muddled, but this time I saw something in the corner of my vision. Grab it! Just grab it! I wedged the floating object under my armpit so that I wouldn’t go under again. Now I had time to try to gather my thoughts and analyse what was happening. I was in the clearest water imaginable, under a sky that almost blended into the blue of the ocean. I realised that what I had grabbed was my surfboard – or what was left of it – but I still couldn’t piece together what was happening. Even with the adrenaline running through my system I was beginning to feel completely exhausted, almost empty. What I did know was that I was in a load of trouble, and I let out a cry, ‘HELP ME, HELP ME!’

Stew pulled up on the jet-ski, and pieces of my memory started to come back together. We had been doing tow-ins, using a jet-ski to whip us into waves earlier and faster. There were a bunch of us taking turns. Stew was shooting out the back of the waves on the jet-ski when he saw my broken board in the water and thought he’d check to see if I was okay.

As he pulled up, he looked puzzled. He didn’t know if this was a joke, given my reputation as a joker. Any of my closest friends would have just laughed at the sight – me hanging onto half a board, hardly moving, as if mortally wounded. Luckily Stew realised the enormity of the situation and jumped off the ski into the water to help me. I was still shouting, ‘Help me!’

But Stew couldn’t hear me – no-one could. I was beginning to drift away again, everything so vivid one moment … then nothing.

Stew yelled out to the others – Prezzo, Greenie, Big Nathe and Crusty – who raced in to help. Greenie was the first to arrive; he’d seen Stew jump off the ski and was already paddling hard, thinking something was wrong with the ski, only to find I was all messed up.

We’d been surfing some random ‘bombie’ waves outside of a break called Thunders, a remote location in the Mentawais, fourteen hours by boat from Sumatra in Indonesia. The conditions were perfect: sunny, not a breath of wind, consistent swell with waves three to six feet high, palm trees in the distance. We were close to the reef, a mixture of volcanic rock and coral, so it’s all razor sharp, and the water was only six feet deep.

The last thing I remember was pulling off the wave and flying through the air …

Now we were in the impact zone with the dry reef ten metres behind us. Unbelievably, the water had gone dead flat. Another wave would have rolled us all and pushed us, along with the jet-ski, onto the reef with no escape, but the surface of the ocean was like a lake. It was eerie.

Whether I passed out through exhaustion or fainted, I couldn’t tell. Maybe knowing someone was there caused the adrenaline to dissipate. I drifted into a dreamlike state; I could hear but I couldn’t see. I thought I was talking, but I had no idea what I was saying.

The jet-ski had a rescue sled on the back – a foam platform, like a massive bodyboard. The boys were struggling to get me onto the sled; I was like a dead weight. I heard someone say, ‘We’ve got to get out of here before a wave comes!’ Greenie got me in a bear hug – I still don’t know how he did it because I’m twice his size – and he threw me on my back onto the sled.

But, still, the ocean was flat.

Greenie then jumped on top to secure me and yelled, ‘Let’s, go. GO!’

We set off for the boat, but we had all been surfing and both Greenie and I still had leg-ropes attached to our boards. Given the urgency, we had forgotten about them, but with the first thrust of the jet-ski the boards acted like an anchor and pulled us both off the back.

Big Nathe was still in the water, and Greenie yelled out for him to throw me back onto the sled while he took our leggies off and stayed with our boards. Nathe got me on in one heave and jumped on top of me as Greenie had.

Stew sped away again and backed off just as quickly once we got out of the impact zone.

As the ski jolted to a halt, I made a shocking discovery. In the ten minutes that had passed, adrenaline running through my body, visions flashing before my eyes and my brain trying to gather my thoughts, I still hadn’t grasped the severity of what had happened.

I was on my back, Nathe still on top, stabilising me, when we abruptly came to a halt and I saw my left leg fly, with momentum, up past my eyes, almost reaching my shoulder. In that split second my focus narrowed in on that vision and I snapped back to reality, realising what I had just seen. I shouted, ‘I can’t feel my leg … I can’t feel anything!’

Big Nathe repeated my words to the rest of the boys.

Whether it was the rush of finally putting together what was happening or my brain going into recovery mode, I fell silent as we raced towards the boat.

I had just experienced an enormous moment in my life. It was Saturday, 20 May 2008, and we were in one of the most remote parts of Indonesia, and breaking my neck was just the start of an incredible journey, a journey where whatever could go wrong, did go wrong …

Help a brother out and buy the book here.