Let's make pro surfing a safe space…

I know a little something about being scared in big surf. More than a little, as in one particular case my obvious trepidation was exposed to peers in the sport’s most public forum.

The year was 1982 and I was in Hawaii competing in the Pro Class Trials at Sunset Beach.

Back then the Pro Class Trials were a pretty big thing, a one-shot ‘QS of its day, through which pro hopefuls qualified for the prestigious Hawaiian events like the Pipeline Masters and Smirnoff Pro, when only the top-16 surfers on the IPS Tour were seeded.

Which meant that along with a bunch of hot young Hawaiians like Mark Liddell and Louie Ferriera and Aussie upstarts like Mike Newling and Steve Wilson, there were guys like me: pretty good surfers who had eked out enough marginal placings at various events throughout the year to earn a Pro Trials invite.

That year, I’d surfed my way through to the main event at the Stubbies at Burleigh, losing to Critta Byrne, and somehow finished fifth at the U.S. Pro at Malibu, seeing my name shoe-horned in among real surf stars like Rabbit, Dane and Shaun. Which is why, come that winter, I found myself standing on the sand at Sunset Beach, wet jersey in hand, shivering in the warm Hawaiian sun.

Like I said, though only a pretty good surfer at the time I had a distinct advantage over some of my more naturally talented competitors: I had Al Merrick’s first Thruster. As in, the first Thruster Al ever shaped, with other CI team riders like Tommy Curren, Davey Smith and Willy Morris all still riding twins. And I put it to good use on the first day of competition, held in four-to-six foot Sunset Point, actually winning a couple heats.

But on the next day Sunset got real, breaking at what everyone but me was calling clean, eight-to ten feet out of the northwest. Which, ignoring the bullshit Hawaiian scale, means the actual size was sixteen-to -wenty feet.

I call that big.

So, I’m ready to paddle out for my third round heat, and all I have to do is place second to get into the Show. I’ve got Al’s second Thruster under my arm, a 7’4” four-channel that Shaun kindly lent me, I’ve got Willy Morris as a caddy, paddling my 7’6” single fin, and, at the sight of those ferocious NW peaks unloading through the inside bowl, a belly full of snakes.

Big day at Rincon? Stoked!

Double overhead at the Lane? Bring it on.

Serious Sunset? Try serious gut wrench.

I was scared, and you could tell because I was uncharacteristically quiet. But I paddled out. Had to. And it went like this.

First wave on the unfamiliar 7’4”, I dropped into a medium-sized inside double-up, landed a bit further forward than I would’ve liked, leaned into the bottom turn, the board tracked straight and I flopped off the inside rail face-down. Rag-dolled until I thought my head was going to explode. Maybe it did. But the leash held, and I came up, dazed but still game.

Second wave, pretty good size with more north in it and an easier roll-in. I actually did a few good turns, racing under the inside curl all the way to the channel. Third wave smaller and fat but I zigged and zagged, imagining I was surfing like Mark Warren.

The answer came with a minute left in the heat. A big West Peak jacked up outside, the biggest set of the heat so far.

I was the only one in position. Except that to me this thing looked like a drive-in movie screen that was about to topple over and crush me, impossibly tall and steep and bearing down on me with what seemed like evil intent. I put my head down and stroked for the horizon as if my life depended on it, because at that point in my blind panic, I believed it did.

“Bradshaw’s winning,” yelled Willy as I paddled past him in the channel, “But one more good one and you’ll get through!” I distinctly remember thinking at the time, “Do I really want to get through? Am I really up to Second Reef Pipe, or worse, Waimea?”

The answer came with a minute left in the heat. A big West Peak jacked up outside, the biggest set of the heat so far.

I was the only one in position.

Except that to me this thing looked like a drive-in movie screen that was about to topple over and crush me, impossibly tall and steep and bearing down on me with what seemed like evil intent. I put my head down and stroked for the horizon as if my life depended on it, because at that point in my blind panic, I believed it did.

Willy broke the spell.

“It’s not going to break!” he screamed. “Take it! Take it!”

A veritable slap in the face. I sat up, spun around and paddled just as hard to catch the monster. I’ll get through the trials, goddammit, and I’ll surf Pipeline and Waimea, too, if that’s what it comes to.

Sure, I was scared, but I was out here, wasn’t I?

Too far, as it turned out.

Paddling again as if my life, or at least my pro career, depended on it, I wind-milled like crazy, but it was no good: my initial flight not fight response had already doomed my shot at the wave of the day. It rolled under me and peeled empty all the way to Vals Reef as the horn sounded, ending my heat and any chance I’d ever have to be taken seriously as a pro surfer.

Later on the beach the announcer read the results, and I don’t remember who it was, only what they said. “Third place, Sam George. Too bad, Sam, but you know what they say, no guts, no glory.” How’d you like that being said about you on the beach in Hawaii, in front of half the pro tour?

Later on the beach the announcer read the results, and I don’t remember who it was, only what they said.

“Third place, Sam George. Too bad, Sam, but you know what they say, no guts, no glory.”

How’d you like that being said about you on the beach in Hawaii, in front of half the pro tour? But, in fact, that’s exactly why I’m telling you this tale.

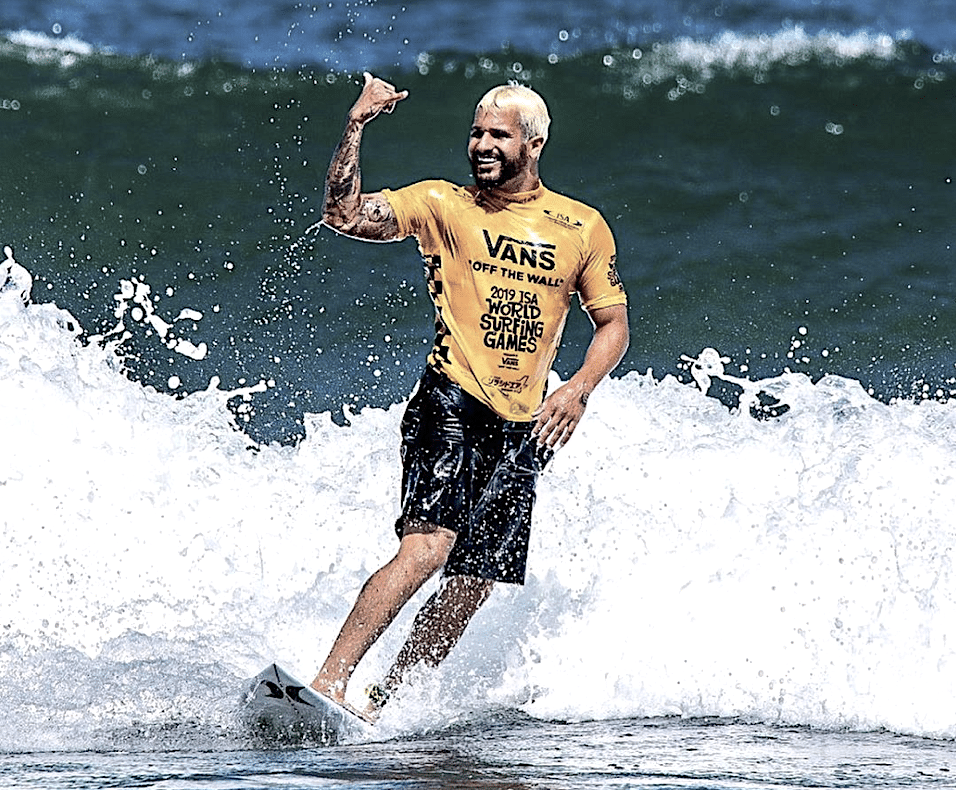

Because while following BeachGrit’s coverage of the Tahiti Pro I read where their resident Critic smugly called Willian Cardoso and Yago Dora cowards for not charging gnarly Teahupoo, but riding only one wave each, and tentatively.

Cowards.

And man, I thought my shaming at Sunset was bad.

At the same time, though, it brought to mind a quote a good friend recited after I told him what happened to me that day, paraphrasing Theodore Rooseveldt, no less:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

Cowards? Scared, maybe. Probably.

But they paddled out anyway, a simple act of courage that those smug Critics, safe on shore, will never understand.