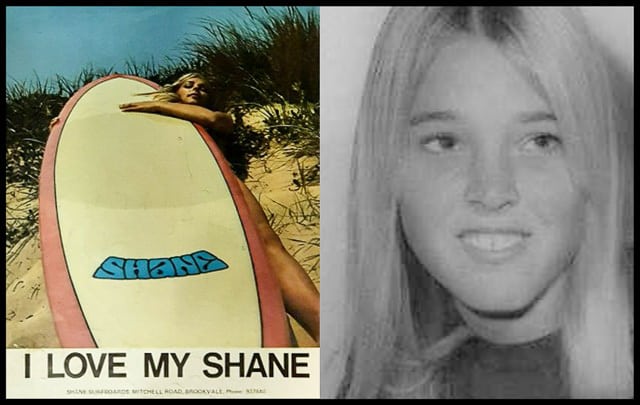

"At 15, just after winning her first national title, Trim was asked to pose naked, on her back, beneath a surfboard, for a full-page magazine ad."

Nat Young’s SURFER Magazine report on the 1969 Australian National Titles, a five-round marathon held that year in Western Australia, mostly at Margaret River, skips completely over the women’s event and doesn’t even bother to post the final results.

(For the record: Josette Largardare won, followed by Nola Shepherd. We’ll skip the men’s.)

This is actually an improvement over Nat’s take on women’s surfing from three years earlier, when he flatly stated that “girls shouldn’t surf, they make fools out of themselves.”

Is it fair to make Young the exemplar of shitty treatment of women surfers during this period? Probably not.

For all that Young built his surfing career on arrogance and bluster and overwhelming force (Bob McTavish described him as “Australia’s answer to Bismark,” and Young’s 1998 autobiography was shyly titled Nat’s Nat and That’s That), he has also proven to be open to change and progress and reinvention. Church of the Open Sky (2019), Young’s second autobiography, finds him in a spotlight-sharing mood, with much love and attention going to his wife and daughter.

On the other hand, from the mid-’60s to the early ’70s the Australian surfing universe revolved around Young like planets around the sun, and if American default position with regard to women’s surfing was to ignore it, the Aussie way to ignore and debase it in equal measure, and Young was certainly on point there—the opening chapter of Nat’s Nat contains a wistful look back at the gang-banging he and his Collaroy Surf Club friends did on the regular with a school-age girl Young identifies as “the Grunter.” Aussie surf-misogyny was truly in a league alone.

Much work remains to be done in simply taking full measure of the injustices, large and small, heaped upon female surfers over the years.

But at the same time, and without reducing or distracting from that injustice, surf history needs to swing its attention to the fact that, barriers and all, women went surfing, and loved it, and that some gifted few—then, as today—were incredibly good at it.

The history they made was barely broadcast at the time, or not broadcast at all. The skill and flair they brought to the game went mostly undocumented. The sport is paying for this still, and will be for a long while.

The mark left on surfing by women in the 1960s and ’70s in many ways consists of the mark left upon them—or, rather, the erasure.

(2020’s Girls Can’t Surf jumped the queue in that it presents the second chapter of a struggle that was engaged two generations earlier. No fault to the Girls producers, though, because good luck finding enough photos and movie clips of women surfers from the ’60s and ’70s to fill out a feature-length documentary.)

So how do we erase the erasure?

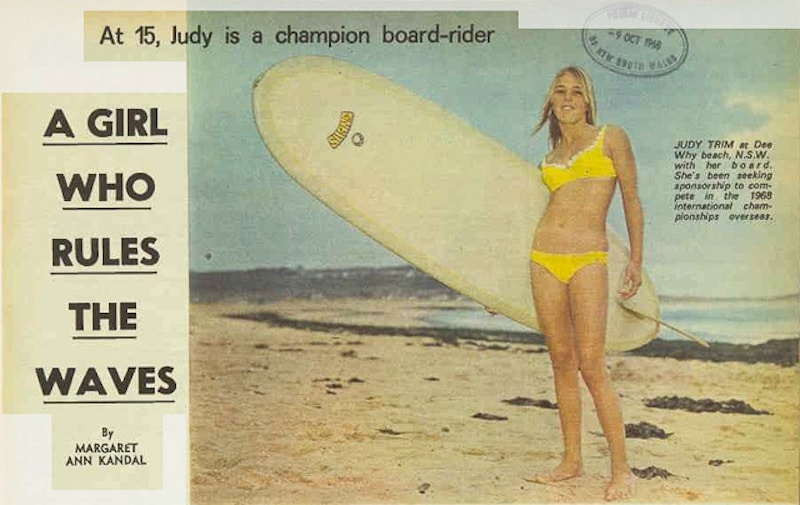

More to the point, how do we raise up and salute Judy Trim?

This is not a rhetorical question. I’m asking as a gatekeeper of surf history who is amazed and slightly panicked at the lack of source material available to fill out a basic Encyclopedia of Surfing page for Trim, two-time Aussie National Champion and three-time qualifier for the World Championships, and possibly the most overlooked and hardest-done-by surfer in the sport’s history.

Nearly everything I have on Trim bends toward indignity. At 15-years-old, just after winning her first national title, Trim was asked to pose naked, on her back, beneath a surfboard, for a full-page magazine ad. She refused, another girl took the job, and Trim claimed that was the end of her board sponsorship.

In 1968, Trim, as the reigning Australian champion, was invited to the World Championships in Puerto Rico. The two top-ranked Aussie men (Nat Young and Midget Farrelly) both had all travel expenses covered. Trim was left to wrangle the funds herself, and the round-trip fare from Sydney to San Juan was steep.

The Aussie team flew off without her. Margo Godfrey, another 15-year-old regularfoot phenom, won the contest—nobody in Puerto Rico was close. Trim would have given Margo a run for the title.

1972, same thing. World title invite extended. No money to pay for the trip. Except by this time Judy had come out as gay, meaning the sport had even less time or interest in her. Trim hung around competitive surfing for another two years, but by 1975, at age 22, she was done, and with the creation of world tour pro surfing about monopolize the conversation for the rest of the decade and into the ’80s, Trim was forgotten before she’d even had a chance to dry off.

So there’s my a grim and depressing little sketch of Judy Trim, and that’s exactly what I’m talking about.

It’s so lopsided. Trim’s story, as told, is important.

But it is also incomplete and buried in grievance and I don’t have the material to go any further, which in a way perpetuates the rip-off. I can’t find a description, anywhere, for example, of how Trim actually surfed. I have zero film footage of her, and just two action photos, both duds.

She was tall and blond, with big front teeth and an easy smile, and I gather from some of the Facebook comments posted after her death, in 2018 (she was 64; cause of death is unclear, but her post-surfing life was checkerboarded with drugs, alcohol, and recovery) that Judy was outgoing, loyal, funny, and smart-mouthed.

How to define Trim more on her own terms, rather than what was visited upon her?

Again, not rhetorical.

Any photos out there?

Did you ever surf Did you ever surf with Trim, or watch her surf, or know somebody that watched her surf?

How good was she; what made her stand out?

From the Facebook comments, I know there was joy and flash and stoke in Trim’s surf life, and that should be given equal time, at least, with the cultural beatdowns.

Here is Judy’s EOS page. It needs work.

(You like this? Matt Warshaw delivers a sassy surf essay every Sunday, PST. All of ’em a pleasure to read. Maybe time to subscribe to Warshaw’s Encyclopedia of Surfing, yeah? Three bucks a month.)